Rebels Without A Cause: The Lost History of 1950's Youth Gangs

- Michael Quebec

- Oct 25, 2020

- 155 min read

"The older generations were especially worried about ‘juvenile delinquency.’ In the 1950’s, this didn’t mean dealing in street drugs or drive-by shootings, but rather chewing gum in class, souping up a hot rod, and talking back to parents.” - Blog, "The Great Nuclear Society: Curing Juvenile Delinquency In The 1950’s,” 2013, reproduced from “The Life Of A 1950‘s Teenager,” by Richard Powers, 2000.

“If I had died then, it would have been for nothing. But if I die now, it will be to clean up the place, for other people to live in.” -

Roger McShane, 16-years-old, in response to death threats following the murder of his friend, 15-year-old polio survivor Michael Farmer, committed by The Egyptian Kings and Dragons street gangs at Highbridge Park, New York, 1957.

Tuesday, July 30, 1957 was a hot night in New York’s Washington Heights district in the city’s West Side.

It was so hot that even into the late evening, teenagers were out and about, mingling, playing ball in the park, and, for two boys, 16-year-old Roger McShane, and 15-year-old Michael Farmer, it was a chance to cool off at the nearby pool at Highbridge Park.

Aerial view of High Bridge Park. The "x" shows the location of where 15-year-old Michael Farmer, a partially handicapped survivor of polio, was attacked by members of The Dragons and Egyptian Kings street gangs. Source: "The Jury Is Still Out" by Judge Irwin Davidson, 1959.

Farmer, who walked with a limp as a result of childhood polio, had been playing rock n’ roll records in his parent’s apartment with his new friend McShane.

A small apartment can be extremely stifling in the summer heat, and the apartment where Farmer lived with his parents was no exception.

The pool at Highbridge Park was closed by 10:30 p.m, but the boys knew of an opening that the neighborhood kids had frequently used to get an extra swim, after hours.

Perhaps the prospect of breaking a rule by sneaking into the pool seemed like a fun and adventurous idea. Perhaps it was a way to bond, and to share in the not-so-well kept “secret” around the neighborhood, as the hole into the pool’s entrance was well known.

Or maybe the kids just needed to cool off. It was a hot apartment.

A week earlier, however, a local gang, The Jesters, made up of primarily, though not exclusively (as illustrated below) Irish teenage boys, had asserted their dominance in the area. Highbridge Park was their “turf,” their territory, and any gang or “bopping club” that wanted to use the pool had better be ready to fight.

This was especially true if the perceived rivals were Puerto Rican.

Members of The Jesters pose for a 1958 article in Life magazine covering the Michael Farmer case.

The Egyptian Kings and Dragons were primarily Puerto Rican and African-American, though there were also a few white members among them. Still, the pool was “off limits” to “them,” not officially by Parks and Recreation of course, but rather, by the code of the gangs.

Some Puerto Rican boys had been beaten up, at least by their recollections, by The Jesters, for simply wanting to take a swim. Now, on this Tuesday night, the combined Egyptian Kings and Dragons had gathered en masse, to run a raid, a “jap” as they called it, on any Jesters who they assumed would be out this hot night.

Though, as previously mentioned, there were some “white boys” among their number, the assumption was that any “Irish” in the Jester’s “turf” must be members of "that club.”

Armed with knives, chains, and a machete, they took their positions behind some bushes with military precision.

The seven members of the allied Egyptian Kings and Dragons street gangs that were actually charged and arrested for the murder of 15-year-old Michael Farmer.

Source: "The Jury Is Still Out" by Judge Irwin Davidson, 1959.

Roger McShane and Michael Farmer, the two boys who wanted to go for a late night swim to escape the heat of a parent’s apartment, were walking into a war zone.

When it was over, McShane, who ran from the attack even while injured, would end up on the critical list at New York’s Presbyterian Medical Center.

Farmer, the boy who walked with a limp, a reminder of his childhood polio, was unable to run.

Previously, there had been 11 gang killings that summer. Michael Farmer was the twelfth.

Mrs. Thelma Farmer, the mother of slain 15-year-old polio survivor (and as a result, partially handicapped) Michael Farmer, hearing the verdict of the murder case for her slain son. September 3, 1959, United Press International.

Debates rage over the reactions to another New York gang killing, the 4th killing in 8 days, 20 deaths since the beginning of the summer of 1959.

Political and religious leaders attack each other in the press over the handling of "the crisis in the inner cities," concerning youth gang-related fatalities.

A monsignor, Joseph A. McCaffrey, presiding over a 16-year-old stabbing victim’s funeral, launches into a verbal tirade before the packed, crowded, Holy Cross Church in Manhattan.

His verbal assault is not only against the gangs themselves, but also against what he sees to be local government and gang outreach policies that favor “coddling."

Excerpts from two issues of The New York Daily News, as well as national coverage by United Press International, of Monsignor McCaffrey's statements while presiding over the funeral of 16-year-old Anthony Krzesinski.

The articles themselves date from August through September of 1959.

McCaffrey angrily states that the gangs should be met “with force” and “caged like wild animals.”

The New York Civil Liberties Union responds, accusing the monsignor of giving free license to police brutality against all young suspects, whether they actually are confirmed gang members, or not.

The NYCLU also sees a potential racial component to the monsignor’s comments.

As for the two 16-year-old victims, friends Anthony Krzesinski and Robert Young Jr. had been stabbed at a local playground by members of The Vampires street gang.

They managed to stumble to their apartments before bleeding to death.

Both boys were not gang members.

Sources: The San Francisco Chronicle, Life, and The New York Daily News, 1959.

One of the accused, 16-year-old Salvador Agron, dubbed “The Capeman” in the press due to the red lined, black cape that he wore at the time of the murder, told the police, “I killed because I felt like it.”

Following the trial in 1960, Agron became the youngest person to be placed on death row in The State of New York.

At the behest of philanthropist, former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, as well as the father of one of the victims, the sentence was later commuted to life.

Agron was paroled in 1979. He passed away in 1986.

September 7, 1959, Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

Another priest, Reverend C. Kilmer Myers, who Monsignor McCaffrey might describe as one of those “coddlers,” had been working to keep the peace between the fighting gangs in the area of Forsyth Street.

The Reverend C. Kilmer Myers during his outreach program, covered in the August 26, 1957 article in Life, "Peacemaking Priest in Gangland."

For three years, the youth activity programs that he oversaw were successful, with athletics and mediation programs that prevented gang conflicts before they started.

But funds were scarce.

According to Myers, The City of New York ignored his requests for more funding to aid in supervised youth activities. The funds would have also enabled Myers to recruit expert social workers to assist in his gang outreach projects.

After three years of peace in the Lower East Side, gang violence exploded again.

Two teenage girls are fatally shot in a drive-by shooting, and a third teen, an altar boy, is wounded.

The Reverend Myers launches into his own tirade, but unlike Monsignor McCaffrey who urged punishment, Myers’ tirade, in the pages of Life, is admittedly, an angry, and frustrated, call for help.

A second photo of Reverend C. Kilmer Myers, from the September 7, 1959 follow up article in Life, "Sportsmen Vs. Forsyths: The Frightful Aftermath."

The article covered the August 23, 1959 drive-by shooting death of 15-year-old Theresa Gee during the gang conflict between The Forsyth Street Boys and The Sportsmen in Manhattan's Lower East Side.

November 2, 1956, San Francisco, California.

The confused, and tearful, parents of a 15-year-old, grant an interview to The San Francisco Chronicle.

Their son, John Alpaugh Jr., had attended a Halloween street party in The Mission District. As the party wound down, he headed home, but was confronted by four boys, ages 18 to 19.

He is stabbed in the chest, the penetrating blade piercing the tip of his heart.

Alpaugh Jr. did not know the boys who attacked him.

In fact, the four boys who would later be charged with "assault with intent to commit murder," were not only unconnected to Alpaugh Jr., they had attacked two other teens that night, 16-year-old Richard Hieber and 17-year-old Benjamin Roybal.

Like Alpaugh Jr., these additional two victims were neither gang-affiliated, nor even acquainted with the the four armed boys.

One of the attackers, 18-year-old Earl Hall, had just been cleared of possession of heroin two days before the attack.

According to court records, then-young Mr. Hall had run-ins with San Francisco law-enforcement since the age of 11, though, according to a San Francisco Examiner story, he hadn’t arrived in San Francisco till the age of 12, after his parent’s divorce in his native Kansas.

That wouldn't be the first inconsistency in the case.

Earl Hall, along with another of the alleged attackers, then 19-year-old Clement Anderson, have surviving “rap sheets” that detail arrests for auto theft and burglary since the age of 10 and 11. Those same rap sheets would cover their “careers” after the 1956 incident, which would include convictions for a drug charge in 1964, as well as additional burglaries and auto theft. (If nothing else, these young men started early, and certainly were ”prolific.”)

Click on each image below for close-ups.

Above are San Francisco news clippings profiling the teen suspects arrested for the 1956 Halloween stabbings. Included in the gallery are surviving documents of arrest, release, and conviction records of two of the alleged attackers, then-18-year-old Earl Hall and then-19-year-old Clement Anderson.

Records date from both prior to the attack, and long after the incident itself. Unfortunately, surviving records for the other two alleged attackers, William Keller and Henry Gorski, both 19-years-of-age at the time of the incident, were unavailable at the time of this writing. Courtesy of The California Archives.

All four, alleged, attackers were on parole from the California Youth Authority, with two, Clement Anderson and William Keller, having spent time at The Whittier Detention Center, and the other two, Earl Hall and Henry Gorksi, at the Preston “Castle.”

"The Castle" was, and still is, a reform school.

The “alumni” includes cowboy actor Rory Calhoun, Beat Generation figure Neal Cassady, and country music legend Merle Haggard. (One thing that could be said of Earl Hall and his criminal record is that, if nothing else, at least he went to the same reform school as the later "Okie From Muskogee.") According to their version of the events, the four (alleged) attackers were “innocent” (aren't they all?) and had been "mistakenly" picked up by arresting officers Dan Driscoll and Henry Pengell, after being identified by eye witnesses.

Anderson and Keller had said that they were performing on stage for the dance that night. (Surviving court records do not state what their alleged “performances” entailed.)

However, in an interview for The San Francisco Examiner, conducted at the Fifth Floor of City Prison, Clement Anderson also stated that he was with his girlfriend at the Century Theater on Market Street at the time of the attack! (In all fairness, theoretically, Mr. Anderson could have been to both events, one after the other, “party hopping.” However, surviving records fail to name a single witness, including his girlfriend, to verify his two alibis.)

All four boys are charged and arraigned at San Francisco Municipal Court, with Judge Charles Peery setting bail for the teenage defendants at $10,000 each. (That would be the equivalent of $95,257.72 for each defendant in 2020 dollars, adjusting the 1956 bail for inflation.)

Alpaugh’s mother tells reporters, “When I saw my son after the knife attack, I thought what a terrible waste. You spend 15 years of your life bringing up a boy, and then you think that life is about to be destroyed.”

Holding back tears, she angrily cries out, “Why do kids do these things to each other?! John is a good boy!”

Looking for an answer, she asks an all-too-familiar question, aware that no answer will come forward.

“Is it our fault?”

Despite the near fatal attack, the young Alpaugh is actually lucky.

Unlike the teen victims of New York gang violence mentioned above, John Alpaugh Jr. survives.

He died of natural causes at the age of 58 on January 6, 2000 in his native San Francisco, the city where, as a teenager leaving a dance party, he was almost killed 44 years earlier.

“The more things change, the more they continue to be the same thing.” - Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, “A Tour Round My Garden,” 1855.

“Perhaps it's good for one to suffer. Can an artist do anything if he's happy? Would he ever want to do anything? What is art, after all, but a protest against the horrible inclemency of life?” -

Aldous Huxley, “Antic Hay” 1923.

"To tell the story of my youth, I like that, it feels good. I feel like I'm sticking up for my generation. It wasn't 'Grease' and it wasn't 'Happy Days.' It was much more complex, and more interesting than that."-

Paul Simon during his interview for his Broadway show "The Capeman."

Why the hell am I writing this thing?!

The idea of writing about 1950‘s youth gangs has been in my head for more than 30 years.

While researching gangs at my high school library, I was introduced to a book titled “The Violent Gang.” (That’s a pretty dramatic title, if to my eyes, redundant.)

Weren’t all gangs, at least occasionally, “violent?”

Well, except for gangs of the 1950‘s and early 1960‘s, of course.

That time period was “the good old days." Gangs of that time certainly never seriously hurt each other.

Those “gangs” that were portrayed in the high school production of the comedy “Grease” (and in the movie version) didn’t hurt each other. They were loveable (and inconsequential) oafs.

There were some “gangs” portrayed onscreen in George Lucas’ “American Graffiti.”

That classic film of growing up and “lost innocence” was a staple of summer syndicated movies here in the Bay Area during my high school years of the 1980‘s (courtesy of KICU TV 36.)

Even though they verbally threatened Richard Dreyfus in that movie, the gang in “American Graffiti” (led by Bo Hopkins, and called “The Pharaohs”) weren’t really “serious.” Hell, the most serious things that they did were minor acts of vandalism that were essentially harmless pranks.

Contrast the image of "harmless" street gangs in "American Graffiti" who "were nothing like the violent gangs of today" with a real-life 1950's/early '60's teen gang member, Salvador "The Capeman" Agron, pictured above. Directly below is a newspaper cartoon illustration, which appeared in several papers in 1959. Unfortunately, the cartoon, and the text, is so over-the-top and sensationalized, that it's easy for modern readers to dismiss the reports as being "exaggerated." The language is exaggerated, but certainly not the acts, as the actual New York case documents, provided below, just under the cartoon, illustrate. (Note, along with the documents, I also received a crime scene photo of one of the victims, Anthony Krzesinski. I chose not to include that photo.)

Upon questioning my teachers at Logan High School, the ones who were the “appropriate age” to have been teenagers between 1955 to 1962 (the “Rock n’ Roll Era”), they assured me that, though what I had seen were works of fiction, “their time” was pretty much like what I saw in those “nostalgic” movies.

Nothing bad, at least, not as bad as what kids of my age group were experiencing, happened during “their time.”

The kids of “their” youth, even the “bad” kids, “were nothing like kids today.”

The teachers who I talked to seemed to be emotionally invested in such statements.

Deep down inside, that always made feel just a little suspicious, as if they were deliberately hiding something from me and my classmates. However, being raised to be a good and obedient Filipino Catholic boy, I put my skepticism out of my mind.

Anyway, questions about the “trouble free” 1950‘s might have been mildly enjoyable, but were inconsequential.

They were “unimportant,” because there’s no way that I, as a then-teenager of the “modern” 1980's, could learn anything about the kids of “my time” by studying about the teenagers of my parents’ generation.

They were "too different from us." The kids who grew up to be my parents’ age came from a "quaint time of innocence."

Or so I was told.

No, I was in the library at Logan High School in 1984, because I needed to know about real gangs.

My high school yearbook picture in 1984. Fourteen, a freshman, and trying to look "tough," and failing, miserably! (The glasses certainly didn't help.)

I was a straight-A student.

As a consequence of being a bookish “nerd” who was up for being a member of “The Golden Key Society” upon graduation (about as “up there” on the scale of teenage “rebelliousness” as being a member of the marching band or the chess club), I was also a tutor.

My counselor told me tutoring would look good on my transcripts when I would apply for college.

I assumed that I would be helping out handicapped kids, kids who were like my brother. He had gone for the first years of his schooling undiagnosed with autism. He also went through hell from his teachers for being “lazy” and “unresponsive,” when he really had a learning disability that the teachers, and the school, were ill-prepared to deal with. (Trust me, this particular theme will relate to some members of 1950‘s-era gang members, later in this blog.)

Instead, to my horror(!), I was assigned to help out the tough kids at Logan High with their homework. That certainly wasn’t my idea.

Many of them were gang members.

The gangs of Union City, at that time, a working-class suburb and former farming community, which is a 45-minute drive South-East from San Francisco, had names like “All Brothers Together” (a gang made up of Filipino-American teens) and “Old Alvarado” (Mexican-American teens.)

So I asked the librarian about books on gangs, just so I can study up on what to expect.

She took me to the library card cabinet file (remember those?) and kindly made the time to help me find the one, and only, book on gangs in their possession.

That book was the aforementioned “The Violent Gang” by Lewis Yablonsky, a psychotherapist who treated New York City gang members before becoming a celebrated author.

The book that started my interest in 1950's and early 1960's youth gang history. I had seen the fictional portrayals in movies like "Rebel Without A Cause" and "The Young Savages," but reading this book was an eye-opener.

When I saw the 1962 publication date, I was disappointed. Well, I was both disappointed and interested. (Talk about mixed feelings!)

I probably should explain why I knew about “American Graffiti” and “Grease” at a time when my classmates at Logan High School were watching “more important” movies about teens that they could relate to, such as “Bad Boys” (the gang banging revenge movie with Sean Penn and Esai Morales, and not the much later buddy action movie with Will Smith and Martin Lawrence) or talking about the one-shot hip hop syndicated tv show “Graffiti Rock.”

Unlike my classmates at that time, I was, and still am, a fan of the 1950‘s. (And allow me to sell, here. My fan obsession for that time became a profession. I taught vintage swing dancing and hosted rockabilly events prior to the pandemic. This is actually my main website for my swing dance classes and events.)

Fandom is an obsession for a specific subject, such as a sports team or a science-fiction franchise.

I’ve admittedly been obsessed with all things related to youth culture from the 1950‘s (and early 1960's) since I was a child. I am a fan of a time period.

I’m not alone, either.

Many fellow “fans” of the 1950‘s meet up every April in Las Vegas at The Orleans Hotel for 4 nights of non-stop (and very loud!) ‘50‘s style Rock n’ Roll music.

Choosing what to read over lunch. (Only a fanboy would bring these to the table while eating!)

So I read the book, just because it was published in 1962, the year that “American Graffiti” was supposedly set. “The Violent Gang” was based on studies with New York teenage gangs between the years 1953 to 1958, which piqued my interest even more.

I remember feeling guilty for “wasting” my time, since I was there to learn about the mindset of the fellow Logan students that my mother used to tell me to avoid, before she herself became a tutor, and did a complete 180 in her views.

I wasn’t there to “escape to a simpler time” by reading about a bunch of uptight teachers wearing bowties, who wanted to cure 1950‘s kids of annoying, but harmless pranks, while blaming the kids’ (very mild) forms of “rebellious behavior” on Rock n’ Roll “oldies.”

To my surprise, the kids of the “innocent” 1950‘s described in “The Violent Gang” exhibited behaviors and mindsets that I had seen, from afar, in those then-modern gangs at Logan!

I expected to read about kids who were “better” in a moral sense, but also unrelatable, to the kids that I was about to work with.

Instead, I read about kids, in this book from 1962, who behaved just like the kids that I would work with. The kids in this book were indeed “violent.” They did use guns on occasion. A few even did drugs.

Everyone my parent’s age, who I talked to at that time, told me, with moral conviction(!) that drugs “didn’t exist” until “the hippie” 1960‘s.

So what the hell was I reading? This couldn’t possibly be real.

I ended up helping out one member of the Filipino gang with his English assignment. (And no, I wasn’t assigned to him because I’m Filipino. He was born here, just like me, and spoke English in the hip-hop based manner that was popular, at that time. Besides, Filipinos were actually the majority at Logan High School in the 1980s. I think they still are.)

That 1962 book helped me to understand the mindset of “the subculture” of the student that I was assigned to work with.

I still had to get to know him as an individual, of course. Gang members are human beings, and no two human beings, regardless of who they “hang out” with or come from are exactly the same.

Also, since the book was a study of 1950‘s “juvenile delinquents” (a term that was popular during that time to describe both gang members as well as any teenager who engaged in some kind of “misconduct”), there were some aesthetic differences between that kid at Logan High School and the kids described in that book.

Obviously, this kid from Logan didn’t wear a “duck’s-ass” hairstyle. The slang that he used was based off of hip hop, as opposed to be-bop jazz (both of which, are from the African-American experience, which I’ll get into later.)

The clothing that this kid wore was of the 1980‘s, not the 1950‘s. (He wore Bogarts, a standard “parachute” pants style popular at Logan High in the early 1980‘s. He didn’t wear Chinos with a garrison belt like his 1950‘s predecessors.)

That said, the swagger, the slow walk which simultaneously said “I don’t give a fuck” while moving to an unheard musical “beat” was there.

The constant, slow grinding motion of his teeth that gave the appearance that he was chewing something inedible, even when he wasn’t eating or chewing anything, was also there. (You ever see a camel chew? Now imagine a camel who’s trying to intimidate you by getting in your face, while chewing. If you can imagine a human version of that, then you get the picture.)

Everything this kid did was either meant to intimidate or “size you up.”

He displayed those outward behaviors and traits, just as described in that library book from the “innocent” era of the 1950‘s and early 1960‘s.

Even more telling, his willingness to settle conflicts physically whenever a “brother” gang member was assaulted was there.

His exact words, when describing an African-American student who had beaten up a “brother” member of the “ABTs” in a one-on-one “fair” fight was, “I’m gonna fuuuuck him up!” (I had to elongate the letter “u” to illustrate the phonetic principles of his pronunciation of that one verb.)

If this makes him sound like some sort of romantic “defender of his people,” it should be noted that he was also just as ready to attack that same “brother” if the latter showed even the slightest signs of emotional vulnerability. He called it “being a pussy,” and if any member displayed emotional vulnerability, especially if it was over a girl, he was just as ready to “be his daddy, and slap the shit out of him,” for the brother member’s own “good,” of course.

That “kid” (who was older and bigger than me) got a B+ on his English assignment, thanks to my help.

He did most of the work. I did not do his homework for him. He was actually very intelligent. Most gang leaders are.

He also later went to jail for shooting a member of a rival Filipino gang in nearby Hayward.

As tragic as that was, when I read that in the local papers, I was just glad that he didn’t shoot me. (And I hope he’s not reading this.)

I shouldn’t have been too worried about that, because I was useful to him. I helped him with school, and he actually told some older boys who were shoving me around in the boys’ locker room, “Don’t fuck with him!”

When he talked, other students listened. It turned out, with good reason. He was very capable of killing.

I went on with my teenage life in the 1980‘s. I had my first girlfriend and made some friends within my brainy social circle.

And, they teased me about my love of “old” music and movies. (I’ve since learned to chose my friends more carefully.)

The girl that I was dating at the time tried to “fix” me by telling me that my love of 1950‘s rockabilly and doo wop was “cute,” but also embarrassing.

“Honey, it’s old, and it’s weak.” I kept quiet. After all, she was good looking, and for a 15-year-old with his first girlfriend, I considered myself “lucky” to go out with someone “above” me. (I don’t think that way anymore, by the way.)

“Old music (1950‘s rock n’ roll) is weak, because art is a reflection of the time it comes from.” (Well, she wasn’t just “hot,” she was also very well-spoken, and also a straight-A student. She later graduated from UC Berkeley, and became a lawyer. And if you’re reading this, I didn’t mention your name, so you can’t sue me!)

“The '50‘s was cute, and quaint, and they didn’t deal with the same problems that we deal with now. So there’s no way that what you listen to compares to what someone like Grand Master Flash or Mel E Mel raps about.” (For readers who are unfamiliar, those were rappers in the 1980‘s whose songs were about social injustice and racism.)

I had some rocker/heavy metal friends, as well.

One of them, while puffing away on a joint while listening to Twisted Sister, teased me with “The '50's was lame, dude. The music was fuckin’ weak, because the people back then were goody goody. They didn’t have to deal with all the shit that we do! That’s what my dad told me. Whenever he comes around, that is. Here.” (He passed me a joint while continuing to criticize my musical preferences and harp on his parents’ divorce. I declined with a nervous smile. I didn’t believe that the ‘50‘s was actually “goody goody,” even though, to my “shame,” I was.)

Many years later, when I started teaching swing dancing at the height of the 1990‘s “Swing Dance Revival,” I was interviewed by the local newspaper, The Argus. The reporter let me know that the “novelty” of my teaching a ‘50‘s variation of swing dancing was “cute.”

However, she also let me know that she was assigned to interview me, in spite of her wanting a more “important” assignment.

Her exact words? “The 1950‘s were quaint. People back then didn’t have to deal with anything important, not like the violence we deal with today. So, the art of that time reflects that.” (She didn’t give me any examples of what she was talking about. For her, anything from that time wasn’t “worth” knowing, even if some familiarity would have helped with an interview assignment.)

My interview for a local newspaper back in the 1990's. I'm grateful that I was able to get publicity, since it enabled my teen dance troupe to get much needed funding for vintage clothing to be used in performances, as well as practice space. However, during the interview itself, the reporter made it very clear that she didn't think much of 1950's youth culture, since, in her words, "It was too cute, too clean, too nerdy, and insignificant."

By the way, we're clearly not dressed in 1950's vintage clothing here for rehearsal. Our practice space was my backyard, in the hot, mid day sun!

Even more recently, before the pandemic, some “friends” of mine in the swing dance world tried to get me to go “contemporary.” There is a modern version of swing dancing called “West Coast Swing” that's done to modern music. I do respect it. (I guess.)

But, my love is for dancing Smooth-Style Lindy Hop to vintage Rock n’ Roll.

My “friends” (and I use the term loosely), with a very condescending tone, told me, “Mike, you’re a wonderful dancer. But you’re stuck with that old stuff. It’s cute, but you can do so much better.”

"Cute."

I told them that there is indeed a market for vintage ‘40‘s and ‘50‘s dancing, aimed at college age students, but my friends shrugged and said, “Well, it’s cute. But it’s a bit too goody goody.”

Again, the derisive tone.

Since, prior to the pandemic, my classes were packed, I decided that any so-called “friends” who put down my art are friends that I don’t need. I don’t care how “well-meaning” their intentions are.

It’s a funny thing about human nature. We respect things that can kill us. We are attracted to things, or people, that are dangerous.

We certainly like things that are comfortable.

But comfortable things, generally, don’t excite us. Comfortable things, or people, don’t earn our respect.

Pop singers who have a reputation for being too “clean and wholesome” don’t get the same airplay or critical recognition that an artist who’s been through rehab and multiple arrests, do.

Sure, it helps if the musician in question actually has musical talent, but a bit of a “bad boy” aura certainly helps. (Remember Donny Osmond? If you do, it’s probably with a chuckle, and as a butt of a joke.)

Perhaps that’s why we’re fascinated with the mafia gangster, the outlaw biker, or the daredevil stunt artist.

Though they are all different and distinct from one another, they seem to be “free” of the rules of society that we sometimes wish we didn’t have to follow, but do, because it’s physically safe to do so.

That combination of attraction, revulsion, fear, and excitement can also be seen in dating.

We know the archetypes, “the bad boy,” “the femme fatale,” “the hot mess.”

Sure, there are “nice guys” and “good girls,” both of which are simplistic stereotypes that ignore the complexity of human beings, but they are convenient labels to illustrate the point.

The “good” (or responsible and mature) dating prospect isn’t as sexually “exciting” as the dangerous sociopath, at least when the two are compared in the media.

When we mature, we know to “run in the other direction” when encountering “the hot mess,” but that still doesn’t mean we aren’t attracted to that person. It only means that we’re more self-aware. For our own well-being, our mature selves resist our self-destructive instinctual attraction for the sexy sociopath.

“Simple,” “innocent,” and all of the other “wholesome” adjectives that are now currently in use to describe the youth culture of the 1950‘s and early 1960‘s make that time out to be “comfortable,” which is great, and maybe even necessary, as we grow older and both the world around us, and ourselves, change.

But unintentionally, that “simple and innocent” perception also makes that time, it’s art, and it’s history seem insignificant.

Nostalgia is the need to escape from the problems of today, but history is it’s polar opposite.

History is the study of people.

I don’t care if someone doesn’t like what I like. No two people are the same and no two preferences are exactly the same.

But, I am a fan.

Fans of sports teams hate it when “their” team is disrespected. (They’ll even fight for “their” team.)

Fans of certain fantasy or science fiction franchises hate it when “normies” (their term for the mainstream) dismisses “their” art form as unimportant. (As an example, fans of the DC comic book icon “Batman” will often get angry whenever the 1960‘s Adam West tv show is mentioned, because in their view, that show made “their” originally “dark” character an object of ridicule.)

That’s the reason for this blog. I’m a fan of 1950‘s Rock n’ Roll-era youth culture.

I want my obsession to be respected.

I’d rather have it be disliked for the “right” reasons, than "liked" for “the wrong” reasons. (And I know that’s both “anal” and makes no sense whatsoever.)

I’d rather someone tell me that she hates Rock n' Roll music because it’s “loud, noisy, aggressive, and sexually suggestive” (actual criticisms that Rock n' Roll and Rhythm and Blues artists faced during rock music's initial thrust into the mainstream during the mid-1950‘s) rather than tell me that she likes '50's "oldies" music, “because it’s sweet and wholesome, like the rest of that time.” (Where’s the fun in that?!)

If showing that the 1950‘s had just as many potentially violent and dangerous youthful criminals, that made their society look at questions of poverty, race relations, mental health, and street crime (just like we do today) seem “worthy” of being taken “seriously”....then (with a sigh) “so be it.”

If I can show that the issues that they struggled with back then are essentially the same that we still deal with today, and thus, still “relevant,” then let the perception, and myth, of an “innocent simple time” be done away with. (I should add that people my age are mentioning how the 1980s were “innocent and simple” times. That should annoy me too, but I’m not in love with “my time” the way I am with the 1950‘s!)

Fortunately, it doesn’t take a lot of “digging” to make my arguments for this “respect by danger” for the years 1954 to 1962.

I would like to thank the following people and organizations, listed below, who helped me out in my research for this project:

Thanks to David Van Pelt, author of "Brooklyn Rumble: Mau Maus, Sand Street Angels, and the End of an Era." His website can be accessed at http://newyorkcitygangs.com/.

Stuart King who runs the “Juvenile delinquent vintage paperbacks! ( jd pulp for some )” Facebook group at https://www.facebook.com/groups/juveniledelinquentfiction.

The administrators at the “San Francisco Remembered” Facebook group at https://www.facebook.com/groups/remembered.

The staff at The San Francisco Main Library showed me how to access their various historical archives, for which much of the information in this blog is derived from. So a big thanks to them. Their website is at https://sfpl.org/.

"Sebastian" (for privacy's sake, no last name) at The California State Archives at https://www.sos.ca.gov/archives/ tracked down juvenile court documents and arrest records, dating all the way back to 1951.

The Aces Car Club of Bellflower, California at http://acescarclub.com was kind enough to grant permission to use their vintage photos, to contrast the difference between law-abiding hot rod car clubs of the 1950's, and fighting turf/street gangs of the same time period.

My good friends Dawn Ishisaki and former professional sportscaster and writer Ron Spain took the time to help proofread this blog for errors. There were many on my part, and considering the length of the blog, there might still be some around. We did our best to remove as many typos and inconsistencies, as possible.

And, I especially wish to thank Gary Jensen, Ben Choate, and Bay Area poet laureate and writer Patrick Coonen. All three gentlemen grew up in San Francisco during the late 1950's and early 1960's. As former teenagers of that time, they were also a part of the street subcultures that are the subject of this blog.

As leaders of their respect groups, their interviews were invaluable to this project.

I want to add that, of course, there were “good” kids in the 1950‘s. They indeed were the majority.

There are many law-abiding and considerate young people today, as well.

Since one of my jobs was to teach teenagers how to swing dance, I can say from personal experience that they are the majority, as well.

This blog is to show the diversity of that time. Experiencing both the "bad," as well as the "good," is the totality of the human experience.

It is my firm belief that if we hold on to the myth of the "innocent days" where "there was nothing serious, unlike what we deal with today," not only do we deny ourselves the opportunity to actually learn from the past, we also deny the existence of the victims of gang violence of that time (and there were many.)

We deny the efforts of the good people of that time, who honestly tried to make living in their communities safer and more productive for the residents of those areas. We deny the efforts, and even the existence(!), of the brave kids who stood up to their peers against violence.

And, we also deny the efforts of those gang leaders who actually tried to steer their clubs away from violence, and towards more constructive efforts (there were a number of them, as well, who "went social," as they called it.)

That myth of "innocent care free times" does not "protect" the reputation of that time. It takes away the voices of those who faced issues that we, as human beings, still struggle with today. (It also diminishes the achievements of those who actually succeeded in bettering their lives, since, if gangs were "nothing like today," in relation to the seriousness of their conflicts, then of course, those who successfully left gang life had nothing of significance to struggle against.)

Nostalgia, unintentionally, diminishes the importance of 1950's youth culture. And if that sounds as if I am actually agreeing with the kids who teased me about my '50's passion in high school, I guess I am (damn it!)

I ask, through this blog, if there is anything from our past that can give us insight as to who and where we are today.

Maybe we won’t have all of the answers.

But perhaps, we can start asking the right questions.

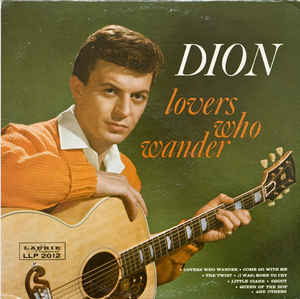

A bit of my non-delinquent, vintage rock n' roll and "clean teen" 1950's and early 1960's collection of vintage vinyl LPs and teen magazines.

Of course, there were good kids in the 1950's and early 1960's. (But, even they are inaccurately portrayed by "nostalgia." )

Dressed in appropriately 1950's/early '60's clothing for a dance demo at a senior center in Berkeley, CA in 2013.

And no, I'm not dressed in a leather jacket and jeans, but the clothing is 1950's!

The young lady dancing with me was one of my former teenage swing dance students.

There is a subculture of young people who research and express their passion for the popular culture of the 1950's and early 1960's. Many of them collect memorabilia of that time, such as vintage clothing, vinyl LPs, and movies. Many of the girls get into pinup photography and vintage hairdressing, while many of the boys get into custom car restoration.

A good number of these young fans study swing dancing (which is how I became acquainted with them), and some are musicians who play vintage jump blues, jazz, western swing, or rockabilly. However, these modern fans are not into "nostalgic memories," nor the aesthetics that accompany the "Fifties Nostalgia" narrative. (In other words, you'll never see these young fans go to a costume shop to buy either a "Fonzie" or cheap plastic poodle-skirt costume for their '50's clothing.)

These young fans want the actual history, which embraces both the glamour, as well as the tragedy.

They want the complete story of 1950's youth culture, not the partial, incomplete, half-truths of "Fifties Nostalgia" embraced by the mainstream.

A word on the the structure of this "blog:" Most blogs are really online articles. This "blog" (and I deliberately put that term in quotes) is really more like a book, in regards to the amount of information, via text and pictures.

I've tried my best to divide sections into chapters, but unfortunately, Wix does not have the option of sectioning off or selecting individual chapters for blogs.

Therefore, readers who wish to reference or skip various chapters will have to do so by manually scrolling.

Individual chapters are separated by full lines.

Individual sections within chapters are separated by smaller lines.

Photos have their own captions, which are separate from the main text, and are also separated by smaller lines.

The captions underneath the pictures are distinct from the main text. To visually distinguish these captions from the main text, the captions will all be in italics. (Hopefully, this practice won't confuse readers, since, from time to time, some words in the main text, such as the names of periodicals, will also be italicized.)

I've also opted to create collages for some of the photos.

For those collages, the use of italics may not necessarily apply, but hopefully, readers will still be able to distinguish the text captions used in the collages from the main text, as the fonts will be different. Finally, in regards to legalities, I've done my best to ensure that the information is true to historical fact.

One thing that is different from today's news reporting, is that during this time period, the names of minors who were arrested for crimes were often printed. Obviously, we don't do that today. That said, with names printed, it was "easier" to confirm whether or not the articles themselves were reasonably accurate via California, Illinois, and New York archival court and police documents. (And those documents, which are available to the general public, do come with a fee, which I shouldered out of pocket!)

Those articles that did not have exact names listed for the accused will not be included here, since the validity of the articles cannot be verified.

Since this is a FREE read, intended for historical purposes for use by general readers, as well as specifically vintage lifestyle enthusiasts and historians (as well as any high school or college students who have to do a history report assignment), I invoke the "copyright disclaimer fair use" notice below, for the inclusion of historical newspaper and magazine articles: "Copyright Disclaimer under Section 107 of the copyright act 1976, allowance is made for fair use for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing."

"Diddly Bops and Jive Studs:"

There is confusion as to what defines “a gang” from the 1950‘s.

In the modern narrative, almost any group of 1950‘s-era teenagers that sported leather jackets or embroidered windbreakers belonged to a “gang.” This has added to the confusion, as well as the perpetuation of the “harmless and innocent” (or “quaint”) myth of some of the youth cultures of that time, when mistakenly describing actual 1950‘s street gangs.

Even people who would have been teenagers during the 1950‘s and early 1960‘s often use the term loosely to describe groups of teenagers from that time, that actually were distinct from what a “real” gang actually was.

As previously mentioned, statements such as the following, are quite common. “Gangs back then, at least the ones that I knew, never hurt anyone. They just liked wearing their gang jackets and working on their cars.” (I personally was told this on several occasions. When I showed issues of Life and The San Francisco Chronicle that contradicted that recollection, then the response was, “Oh, well I never heard about that. I didn’t hang around gangs. But, I was there.”)

A social club of teens, who organized dances and athletic events for their fellow teens in their community, and who wore windbreaker jackets with their club name embroidered on the back, are remembered under that term, and yet, this example clearly pertains to a non-violent and non-fighting “social club.”

Often, a person within the 70s to 80s age range, looking back to their pre-teen and teen years, can (and do) remember these “gangs” as “harmless kids.”

They’d be right in remembering them as harmless, but, mistaken in assuming (or “remembering”) that all, or most, “gangs” of “their time” behaved as benignly as these (mislabeled and miscategorized) teen social jacket clubs.

One example of a 1950’s teen social club would be “The Social Lions” (pictured below), a former fighting gang that, as their name obviously states, “went social,” thanks in part to the gang outreach organization The New York City Youth Board.

Prior to the intervention of that organization, “The Social Lions” had been a “real” fighting gang during their early history, under the name “The Knifers.” (That name should tell something about what they used to be like. Subtlety wasn’t exactly high on this particular groups’ list of priorities when they first chose their name.)

Source: Reaching The Fighting Gang, The New York City Youth Board, 1959.

Another type of jacket wearing organization of young people that existed during the 1950‘s were the car clubs, the “hot rod clubs,” that were popular throughout the U.S., but were especially prominent in Southern California, where dry lake beds and abandoned runways helped that subculture to grow.

These car clubs, which were also distinct from the fighting gang or “bopping club” (more on that term in a bit) sometimes dressed in an outwardly similar manner to the Hollywood stereotype of a “juvenile delinquent.”

Car clubs of the 1950‘s often consisted of young members, though, not exclusively teenagers. (Hot rodding had been around for decades, but the specific clubs that flourished in Southern California in the 1950‘s were actually started by returning World War Two veterans in the later half of the 1940‘s.)

Self-identified “hot rodders” also, occasionally, had run-ins with the law, due to the practice of street racing.

Hot rod club organizers however, sought to “clean up” the image of hot rodding in the public mind, and would work with law enforcement to curb illegal street racing. The National Hot Rod Association, for example, cooperated with law enforcement towards that end.

However, hot rodders, whether they were actually members of the car clubs, or not, were often perceived by the general public, at that time, to also be “juvenile delinquents,” due to street racing fatalities and the resulting, unwanted, police attention from rogue members, acting in defiance of the official policies of the clubs.

Unlike the fighting street gangs that existed at the same time, legitimate car clubs (such as The Aces Car Club of Bellflower, California, with their club jacket pictured below, as being one example) were generally benign, generally law abiding, youth hobbyist organizations, at least when compared to the "bopping clubs" (street gangs who fought over turf) of the inner cities.

Source: The Bellflower Aces Car Club website at http://acescarclub.com (Picture is used with permission.)

Adding to the confusion for the mainstream (adult) public of that time, was the younger members’ of the car clubs use of the same, or at least comparable, slang colloquialisms, which were based on the slang of African-American Jazz musicians. (In short, they “talked” like gang members.)

Obviously, car clubs were concerned about the artistic aesthetics of their cars (if they were custom clubs) or how much initial speed they can get out of a specialty car that was worked on (if they were involved in hot rodding and drag racing.)

Was there occasional “crossing over,” as in an individual being a part of both car culture and fighting street gang culture? Yes. I interviewed one gentleman who was a part of both. However, that gentleman made it clear that he was a part of both subcultures, and that the two were distinct.

I’ve yet to find any evidence in my research that a Southern California custom or hot rod club, as a formally organized group, engaged in “rumbles” over “turf,” though I have found evidence of drive-by shootings by actual 1950's Los Angeles gangs who used fast cars. (But of course, their cars weren’t exactly hot rods used for drag racing. They were used for “getting away.”)

That acquaintance who looked back with vague fondness for the Southern California car club that she remembered as “a gang” was (sort of) “correct” in assuming that the “gang” she remembered was “harmless.”

However, this blog is not about “social clubs” nor “car clubs.”

Our specific focus is on the “bopping clubs,” the fighting gangs that formed the real-life basis for the fictional “juvenile-delinquent” of Hollywood movies, such as “West Side Story” or “Blackboard Jungle.” (The latter movie, though a personal favorite, does have a street racing scene where hot rodders knock over another car, nearly injuring Glenn Ford and Ann Francis. The movie itself was about youth gangs terrorizing teachers in an inner-city high school, and the implication was that hot rodders and genuine gang members were practically indistinguishable.)

Before we define what a gang is however, we should briefly touch on why certain kids, in certain areas of the U.S. during the period immediately following the end of World War Two, joined or formed fighting street gangs.

Once we understand that, then it’s easier to define what a gang exactly “is.”

Ratpacking:

“When I look back on the days that I was with the gangs, I remember those young men who cared about how they looked and who had a great deal of honor and ethnic pride.” -

Nestor Llamas, former member of The Simpson Street Boys in an interview for the History Channel documentary “Gangs: A Secret History.”

Source: The San Francisco Examiner, November 21, 1959.

1956 Senate Subcommittee Hearings on Juvenile Delinquency. The hearings from two years earlier are covered later in this blog. However, the 1956 hearing, and it's results, are referenced in a blog from The Center On Juvenile And Criminal Justice's website.

Click on the picture of the hearings' report above to access that blog (after you finish reading mine, of course!) *On a personal note, this 1956 report is much more reasonable and "sobering" than the one from two years earlier. That 1954 report will be covered later.

School has always been hard for certain kids. It was true then, and it’s true now.

A child or teen could be a highly intelligent person, with a genuine desire to learn. But if he or she has a learning disability, it’s difficult to keep up in a group class setting, where learning is often tailored to the group, as opposed to the individual.

If a student is a recent arrival, and struggles with the English language, that student could also be highly intelligent, but still have a hard time keeping up.

In the 1950‘s, recognition of certain learning disabilities in the public school system was non-existent.

If a child or teen had dyslexia, he or she was out of luck, because the condition simply wasn’t recognized at that time. I personally worked with a senior citizen who had dyslexia. Relating his high school years between 1959 to 1962, he stated, “It was hell. They put me in with the retarded kids!”

Bilingual education was not in place until 1958.

Prior to that year, if a student was newly arrived from Puerto Rico, he or she was also out of luck. (I should add that Puerto Rico has been an American commonwealth since 1898. Puerto Ricans are American citizens, and have been since 1917. Arguments about “Go back to your own country if you don’t speak the language,” which were directed at Puerto Rican migrants by some bigoted individuals during this time period, is absurd, in my opinion.)

Teachers in Northern cities were not supposed to act discriminatory towards students based on ethnicity. But often, during the 1950‘s, some teachers behaved in ways that would be referred to today as “culturally insensitive.” (And honestly, some were just outright bigoted.)

One African American youth gang leader, who actually scored high on i.q. tests, related in an interview with Lewis Yablonsky (author of "The Violent Gang") that his home room teacher often singled him out for assignments that were beneath him. This would be an example where individualized attention in a group class setting was actually not wanted. With a feeling of being “talked down to,” he found another outlet for his high intelligence, by becoming a leader or “president” of a youth gang.

Kids who joined inner-city gangs in the 1950‘s came from working class families. Usually, they were the descendants of either immigrants (examples being Irish or Italians, who also faced bigotry upon their arrival a generation before), or the children of migrant, working class families who were recent arrivals from one part of the U.S., into another, and were seeking employment.

Some were the children of the previously mentioned Puerto Rican migrant families. “The Great Migration” of Puerto Rican working class families occurred in the late 1940‘s and early 1950‘s.

Puerto Rican workers sought mainland employment, after the economy on the island switched from agriculture based on sugar production to factory-made exported goods and high-end tourism.

Jobs on the island became severely limited during that shift. A growing population didn’t help. Puerto Rican workers were encouraged to migrate to New York by certain mainland politicians as a “source of cheap labor.”

For close ups, click on each picture.

The August 25, 1947 issue of Life covered the influx of Puerto Rican migrants into New York City, in the wake of "Operation Bootstrap," the shifting of the island's economy from sugar-based agriculture to manufactured exported goods and tourism.

Puerto Rico itself is an unincorporated territory of the United States. So, as noted, Puerto Ricans were, and are, American citizens. The title of the article correctly avoided the use of the word "immigrant," as that would be inaccurate.

Many African-American families, leaving the Jim Crow segregated South, migrated to Northern cities such as New York, Chicago, and Oakland to work in the munitions factories during World War Two.

Of course, they ended up staying in those cities when war production ended. They continued to seek employment, often with frustration, with the hope of a better life than what they previously experienced in the segregated South.

Segregation may not have been “legal” in New York, at least, not in the same way that it was in places like Birmingham, Alabama, but, as pointed out in the June 26, 1956 issue of Look magazine (pictured below), segregation and discrimination were very common in the North in actual practice, if not on paper.

Look magazine covered unofficial segregation in Northern cities with this article, "Jim Crow Northern Style."

Segregation in the North may not have expressed itself in the form of signs stating "colored only" or "white only" as displayed in the South, but as shown in the article, in actual practice, many qualified African-American professionals were denied access to jobs and homes that they would have had, if they were of European descent. Denial of service to African-Americans in restaurants, hotels, and other service areas was also common, if technically "illegal," in the North.

* In addition to the story on Northern racial discrimination, this issue of Look, cover dated June 26, 1956, also carried a story on the then-"controversial” teenage fad for rock n’ roll music. (That separate article addressed concerns about the music’s possible “influence” on juvenile delinquency, a subject that will be explored later in this blog.)

Puerto Rican and African-American working class families found themselves “hemmed in” in the inner-cities, and often in competition for jobs, living space, and resources, both with each other and with Irish and Italian-Americans, who themselves had also faced bigotry.

Irish and Italians may have been “white,” but they (generally) were also Catholic, with distinct cultures that often separated “them” from mainstream society.

For close ups, click on each picture.

The marginalized of American society: Separated and excluded from opportunities in the "legitimate" world of the mainstream, their children were susceptible to joining, or forming, street gangs in the years following the end of World War Two, and into the 1950's. Top, left to right:

Anti-Irish propaganda by the Ku Klux Klan, 1926.

Ku Klux Klan Anti-Italian and Anti-Catholic propaganda, circa 1920's.

Americans of Irish and Italian descent may have been European, but they were often treated as second-class citizens, and viewed with suspicion (due to their practice of the Catholic faith) by the American mainstream. Bottom, left to right: 1943 debate over the repealing of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.

1955 coverage of the previous year's (1954) "Operation Wetback," in which approximately 1,074,277 Mexican migrants, many of whom were actually U.S. citizens, were "deported" back to Mexico.

Source: Newspapers.com.

As an example of this “difference,” when John F. Kennedy was elected president in 1960, in addition to his youth, another aspect that many Americans found “unique” or even “novel” (and for some, “offensive”) was that he was an Irish Catholic American president.

On the East Coast, the primary, though certainly not exclusive, ethnic makeup of the teenage street gang was Italian, Puerto Rican, African American, and Irish.

Their ages generally ranged from 14 to 18.

The Fordham Daggers and The East Harlem Red Wings (Italian), The Mau Maus and The Egyptian Kings (Puerto Rican), The Chaplains and The Sportsmen (African-American), and The Jesters and The Norsemen (primarily, though later, not exclusively, Irish) would have been examples of 1950‘s teen gangs from New York.

The violent, and often fatal, conflicts of these specific gangs would garner national attention in the pages of The New York Times, The New York Daily News, and Life magazine. United Press International would also cover their stories, which would be reprinted in various local newspapers around the country.

Sources: UPI/San Francisco Chronicle, August 31, and Life, September 7. Both articles are from 1959.

On the West Coast, along with Italian, Irish, and African American, the ethnic composition of teen gangs also included both the children of Mexican immigrants and the children of Chinese-American working-class families.

Los Bandidos, Los Gavilanes, and The Latin Quarters would have been examples of primarily Mexican-American youth gangs during that time, with the first two from San Francisco, and the last from Los Angeles.

Los Gavilanes, a mixed Mexican-American/Puerto Rican gang of teens, would figure prominently in local headlines in The San Francisco Chronicle, both for “rumbles” with other teens, as well as a December 7, 1958 robbery and assault of a 63-year-old retired army sergeant in the Fillmore District, allegedly committed by four of their members. (And, in all fairness, when Las Gavilanes decided to "go social" and renounce violence, they also explained to both The San Francisco Chronicle, and the youth outreach program "Youth For Service," about the motivations and reasons for the rivalries of the various gangs, including their own.)

The Latin Quarters gained both local, and national, notoriety in the pages of The Los Angeles Times, and The United Press International, in 1957. Their feud with The Florence Gang (also Chicano) resulted in several deaths, including a confirmed, "accidental," drive-by shooting of an 18-year-old girl.

The Lonely Ones were an example of a primarily, though not exclusively, Chinese American gang out of San Francisco, many members coming out of Galileo High School, where they apparently had a skirmish with The Junior Jokers, a mixed working class youth gang, sometime between 1958 and 1959. The Lonely Ones are mentioned in several issues of The San Francisco Chronicle. Like Los Gavilanes, they are featured both for alleged violent crime, as well as for working with Youth For Service.

The Savoys would be an example of a 1950‘s African-American teen gang out of San Francisco, specifically Hunter’s Point, where their confirmed, violent encounters with other youth gangs, such as The War Demons, gained local attention in several issues of The San Francisco Chronicle between 1958 to 1961. Another 1950's-era African-American teen gang out of the Bay Area would include The Sheiks, who's club jacket is pictured below, in the gallery of West Coast youth gangs of the 1950's and early 1960's.

For close ups, click on each picture.

West Coast Mobs...'50's Style:

California, particularly San Francisco, Oakland, and Los Angeles, had it's own teen gang culture that was comparable to, though also distinct from, that of New York. San Francisco street gangs, however, garnered more local, rather than national attention, though the Bay Area had it's own share of shootings, stabbings, beatings, and robberies committed by minors, as reported in The San Francisco Chronicle and The San Francisco Examiner. (And I should add, backed by existing court documents provided by The California Archive.) Los Angeles, however, did receive national coverage in late 1957, with the drive-by shooting death of 18-year-old Emily Guzman (see both the chapter on "Weapons," as well as the end chapter on "Barts and White Shoes" for more in-depth information on both California street gangs, and teen gun violence, in the 1950's, respectively.)

A teenager in an inner city, who generally didn’t do well in school (for a variety of reasons), and came from a working-class family, could be a likely candidate for gang membership.

An inner-city teen whose family was not only financially struggling, but also had to deal with racial discrimination, could also, potentially, consider joining a gang.

A boy who lived in a single parent household in the inner city, because his father had been killed during World War Two or The Korean War, or had abandoned the family due to financial struggles, could also find a sense of “meaning” and “belonging” in a street gang.

And of course, a kid who simply needed protection from bullying by a gang in a crowded and impoverished inner-city neighborhood would find protection by joining a rival gang.

These were rough kids in a rough environment.

If school couldn’t, or wouldn’t, allow these kids to feel a sense of accomplishment, or belonging, the gang could.

The gang also represented a way for these impoverished kids to gain prestige.

In an environment where financial prospects were few and far between, a sense of self-importance by displays of courage during violent conflicts was one way for a young man to prove his “manhood,” to display that he had “heart.”

Nestor Llamas, who had been a member of a 1950's-era Puerto Rican youth gang known as "The Simpson Street Boys," related these feelings for the History Channel’s documentary on gangs.

Llamas stated, “I felt that I was a part of something bigger.”

In the end, a lot of these kids joined gangs because they were poor, and gang fighting, at that specific time in their lives, was a way for them to show that they mattered.

In the introduction, I mentioned the 1962 book, “The Violent Gang,” based on studies with New York youth gangs. I am bringing it up again, because of it's title.

Though an excellent resource, I think a more accurate title could have been “The Prestige Gang.”

Prestige, their “rep,” along with a sense of belonging, were the main reasons why these kids joined the gangs.

“Rep” and proving that they had “heart” (courage and loyalty) for their “brothers” (fellow gang members) were what these kids fought for. And they fought for the protection of their “turf,” the few square blocks of their neighborhood that was “their” territory to “protect” from “invasions” from other gangs. Sometimes, those invasions were real, as when kids from other neighborhoods would come in to physically assault the local kids either for “kicks” (fun) or to steal from them.

They were all poor kids who had to literally fight for what little resources were available.

To them, “turf” and “rep” were all that they had, and they often died in defense of both.

This map, detailing the "turf" of various New York gangs, appeared in the June 15, 1954 issue of The New York Daily News. The map was actually incomplete, as there were many more gangs in the area that were not listed here.

Walking The Walk And Talking The Talk -

(The quote was derived from a line in a June 1921 Ohio newspaper describing a watchmaker who gave the impression of being a brave hero.)

Glossary of New York gang slang, from the 1959 handbook "Reaching The Fighting Gang," by The New York City Youth Board, a gang outreach organization.

Youth gangs of the 1950‘s, like any teen subculture, had their own language, style, rituals, and even mindset.

The language of 1950‘s youth gangs was a combination of phrases inspired by African-American based Jazz and Rock n’ Roll music colloquialisms, as illustrated above.

These were mixed in with World War Two-era inspired terminology. (Perhaps “bastardization” or “corruption” might be a more accurate description for the colloquialisms used by these gangs.)

From African-American music culture, the terms “bopping” or “bop,” as well as “swinging,” “swing,” and “jitterbugging,” all terms that originally referred to partnered swing dancing based on the Lindy Hop, became terms used in inner-city gang culture to signify “fighting” (and various forms of fighting, at that.)

One thing that we should get out of the way now is the term “gang.”

During this time period, “gang” or “gangs” was a term used by the adult mainstream (the press, teachers, parents, religious leaders, politicians) as well as “straight” teens who were not a part of gang culture.

The gangs themselves hardly ever used the term “gang.”

They usually referred to themselves, and each other, as “clubs.” (As related earlier, this has led to confusion between these gangs and the similarly attired teen social clubs and car or hot rod clubs.)

To signify their distinction from clubs that had gone “social,” the fighting gangs referred to themselves as “bopping clubs.” For our purposes, and for most of the remainder of this blog, the New York inner city youth gangs that engaged in intergang conflict for the “protection” of their “turf” (area that the gang members claimed as “theirs”) shall now be referred to as “bopping clubs.”

Alternatively, San Francisco-based fighting gangs shall usually be referred to as “jacket clubs.” These distinct terms are locally based.

New York gangs of the 1950's often referred to each other in press interviews as “bopping clubs,” but I have not found that term used in interviews with San Francisco-based youth gangs of the same time period. I have found instances where San Francisco gang members, interviewed by the gang outreach program “Youth For Service,” referred to each other as “jacket clubs," though another term that they often used was "Barts."

That term, along with "White Shoes," both of which referred to distinct sub-cultures of Bay Area 1950's teens, is explored in depth in the chapter on "Barts and White Shoes," near the end of this blog. A third subculture of 1950's teen street culture from San Francisco, "Muns," is also mentioned in interviews, but further information was unavailable at the time of this writing. Pachucos, a sub-culture of Latino teens, left over from the 1940's "Zoot Suit Riots" era, did continue in both Los Angeles and San Francisco into the 1950's, and that is also explored further in the end chapter on San Francisco gangs.

The slang terms sampled above from The New York City Youth Board’s handbook are primarily examples from the influence of African-American music culture.

The military-influenced terms used by the bopping clubs include the notorious (and racially inspired) “jap,” which refers to a surprise raid by a few members of one club into another clubs turf. The idea was to get in quickly, cause as much physical damage to a rival club’s members in ambush fashion, then get out of the turf quickly before getting caught. The term is obviously a reference to the raid by Imperial Japanese air and naval forces upon the U.S. Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, which propelled America’s entry into World War Two.

The term is confirmed by Nestor Llamas in a History Channel interview for the documentary “Gangs: A Secret History,” and is included in the excerpt below from Harrison Salisbury's 1957 non-fiction book "The Shook Up Generation" (and to add authenticity, it was later used in Evan Hunter's fictional "A Matter Of Conviction," published in 1959.)

Source: "The Shook Up Generation," Harrison Salisbury, 1957.

Other military influenced terms used by the “bopping clubs” included references to “squads” of different distinctions (“suicide squads,” “garrison belt squads”) and “divisions.”

Structure of the New York-based bopping clubs were along pseudo-militaristic fashion, with grandiose sounding titles that elevated the status of these working class adolescents. “President,” “vice president,” “war lord,” “war counselor,” and “emissaries” were just some of the examples that can be found in the press, court documents, and gang outreach notes. It was very common for these kids to introduce both themselves, and each other, to adult authorities by their titles in the clubs.

These “official” titled introductions would both amuse, and shock, law enforcement, the press, and local officials when these kids’ names were given in official contexts. (Judge Irwin Davidson, presiding over the Michael Farmer murder case in 1957, was taken aback when 16-year-old murder suspect Louis Alvarez, under oath, referred to himself as the “warlord” of the allied Egyptian Kings and Dragons clubs.)

The "Look," Street-Wise "Fashion Sense" in the 1950's Gang World

Click on each photo below for close ups.

Top:

Garrison belt ad, 1957, part of a "Mess Sergeant Play Set."

Bottom, left to right:

Bates shoes ad, 1959.

Chino tapered-style pants ad, 1957.

Boy's hat ad, 1959. Source: Newspapers.com.

The “uniforms” of the gangs gave unity and furthered their sense of belonging, both to the bopping club, and to the street culture.

Of course, there was the Hollywood stereotype of the leather jacket, blue jeans, t-shirt, and motorcycle boots, made famous by Marlon Brando in 1953‘s “The Wild One,” and also worn by the fictional “Wheels” gang led by Corey Allen in the James Dean vehicle “Rebel Without A Cause” (1955.)

Some boppers certainly did dress in that manner.

Angel Luis Velez, the teenage “author” of the threatening letter, sent to the Spanish-language New York newspaper El Diario, promising a gang "war" on the New York Police Department if members of The Egyptian Kings and Dragons were prosecuted (and executed) in the Michael Farmer case, is seen wearing that style in the 1958 photograph pictured below in the gallery.

However, like most “nostalgic” recollections of the 1950‘s, the popular stereotype of the leather jacket and blue jeans overshadows a much more diverse and varied reality. The Marlon Brando Hollywood-inspired look was simply one, of many varied ways that members of bopping clubs dressed.

Some boppers dressed very “stylishly,” with tapered slacks (such as Chinos, pictured below), dress shirts, thin ties, and overcoats. Central Harlem African-American bopping clubs of the mid-1950‘s even took to wearing grey flannel dress suits, in imitation of the similarly dressed “Madison Avenue Mad-Men” (as featured in that AMC historical drama.)

A fedora or stingy brim hat, with sunglasses, finished that “high classed gangster” look.

Bopping clubs who sported a “high class” fashion sense (that was completely the opposite of the Hollywood jeans and leather jacket stereotype) included The Viceroys, The Robins, The Young Stars, The Beavers, The Tiny Tims, and The Brownsville Black Hats.

There actually were two Hollywood movies from this time period that accurately portrayed this alternative “sharp” fashion sense. The first was 1959's "Cry Tough," starring the late John Saxon and Linda Cristal, and the second was 1961‘s “The Young Savages,” both of which will be covered in the later chapter on "JD" movies and novels.

Garrison belts were a popular, and functional, fashion accessory. The buckles were often sharpened and used as weapons when swung. (Hence the term “garrison squad,” which were “units” of club members specifically armed with these belts.)

Chino pants were (and still are) a straight leg trouser that are pegged at the bottom. They were popular with teenage boys of that time, both by members of the bopping clubs, as well as by the "civilian" non-gang teens. Boppers liked the tapered or "pegged" slacks and trousers for their “stylish” look. Other boppers took to the (cheaper) slim Levis for the same reason.

Big Ben trousers were also a favorite brand of pants in the 1950's, particularly in San Francisco. Members of the embroidered jacket wearing gang culture of San Francisco that most resembled the Hollywood stereotype of the "juvenile-delinquent" were referred to as “barts” during this time, and the wearing of Big Ben trousers was one way that they were identified by that term.

Bates floaters also emphasized a fancy “sharp” look, in regards to footwear, which contrasts to the stereotypical motorcycle boots (which some boppers did indeed wear, especially for "stomping," kicking an opponent when he's down.) Bates floaters, on the other hand, were made of soft leather. According to Ed Bielcik, a former member of The Sinners, they were "Lousy for stomping...great for running like hell!"

Bopping fashions served a psychological and a practical function.

As the children of the working class, dressing stylishly announced to the world that they “made it” and that they were important (at least within the context of the gang world.)

Also, in some cases, sharpened articles of clothing, such as the garrison belt, were actually used as weapons.

Even the stereotypical leather jacket served a functional use for the bopping club, a use that was lost on the upper-middle class teens who later, as a fad, imitated and appropriated the look as a mild form of “rebellion” against the adult world.

Apparently, these black leather motorcycle jackets deflected knife cuts.

The Hollywood stereotype of "The Juvenile Delinquent." Marlon Brando popularized the look of the leather jacket, jeans, and motorcycle boots in 1953's "The Wild One." Actually, he played a young adult leader of a biker gang, loosely based on an incident, blown out of proportion in the press, that occurred in Hollister, California in 1947. Though the character of "Johnny" wasn't a teenager, teens quickly adopted the "uniform" of the leather jacket and jeans in imitation of the film as a sign of "rebelliousness." This included both middle class teens who wanted to "look tough" (but weren't really "gang members") as well as, occasionally, members of real "bopping clubs." (From my personal collection.)

The fad by 1950's-era middle-class teens for dressing up like a juvenile delinquent "rebel" in order to "look cool" was nothing new, or even exclusive, to the 1950's. (There are upper-middle class teens today, who both dress up, and affect the speech pattern, of inner-city hip-hop culture.)

However, as we'll see later, this "posing" and appropriation by the youth of the middle class often confused, and even frightened(!), many adults, particularly authority figures, during the 1950's. The black leather jacket and blue jeans worn by Marlon Brando in “The Wild One” and James Dean’s opponents in “Rebel Without A Cause” were also, occasionally, worn by middle class teenagers, as a fad inspired by the movies.

These were teens who never formerly belonged to a true bopping club (i.e., a teen organization that patrolled their “turf” and engaged in “rumbles.”)

However, since these were what mainstream adults, at that time, perceived to be the clothing of the bopping club, many adults in positions of authority were convinced that “juvenile delinquency” was a threat, seeping out of the inner-city, and into their middle-class suburban neighborhoods.

Simultaneously, those upper middle-class, non-gang teens (who appropriated one aspect of clothing worn by bopping clubs) experienced their parents’ or teachers’ “paranoid” fears, and, into their adulthood, “remembered” the “irrational hysteria” of juvenile-delinquency of the 1950‘s, especially in connection to rock music culture.

In other words, both the adults and teenagers of the upper middle-class mistook, and overestimated, the significance of the surface aesthetics of gang culture, in their own ways.